Hogwarts Legacy is here, its arrival surrounded by more brutal blasts of discourse than there are bursts of Bat-Bogey Hexes flying around the Slytherin Common Room. The conversation around the open-world action adventure game which seeks to provide players with the immersive fantasy of actually attending the storied school of magic from the Harry Potter universe, largely stems from the fact that the universe’s creator, J.K. Rowling, is a virulent transphobe, using the platform afforded her by her fame and wealth to normalize the othering of trans people and contributing prominently to a culture in which anti-trans sentiment, legislation, and violence, are on the rise.

However, the conversation doesn’t start and end there. As game sites and critics have struggled to navigate how to cover the game, conflicting ideas about the very nature and role of criticism have also been conjured and flung about.

Some have argued that the right way to cover Hogwarts Legacy is not to cover it at all. I respect this viewpoint, but I don’t share it. I think that the cultural impact of the game is so vast, and the issues swirling around it so important, that it demands thoughtful critical engagement, and that requires playing the game. So I prepared to take the unusual step of enrolling at Hogwarts as a fifth-year.

Harry Potter and me

Before I get to the game itself, I want to be clear about my relationship to its world. Normally I wouldn’t go to such lengths, but given the intensity of the conversation around the game, I think it’s important that readers understand where I’m coming from.

I read the Harry Potter books around the time they came out, back when I was blissfully unaware that J.K. Rowling would one day become known as much for her transphobic ideology as she is for being the author of an outrageously popular series of children’s books. (I am trans, which makes her attitude about trans people particularly hard to overlook.) I was already older than the series’ target audience, but I liked them fine, and thought that they deserved to become new classics of children’s literature.

I understand the appeal of a game like Hogwarts Legacy–the chance to step into an immersively detailed recreation of a place one loves from books and films and craft your own compelling story by attending classes, making friends, learning spells, getting into mischief, visiting Hogsmeade, exploring the castle, and finding yourself at the heart of a conflict that threatens the wizarding world. As a player and a critic, I approached all of that with an open mind.

At the same time, I’m not a die-hard fan, steeped in Potter lore. While I remember the broad strokes of the series’ narrative, I’ve forgotten most of the smaller details, so I’m not going to catch every reference and Easter egg. I know that the Weasleys I’ve met are ancestors of the ones in the books, sure (Hogwarts Legacy takes place in the 1890s), and I recognize plenty of other family names and nods to magical dynasties, but for every reference I catch, I’m sure that a dozen fly over my head.

I’m not here to judge how well Hogwarts Legacy crams in bits of fan service. Just as I think a good Star Wars game or The Lord of the Rings game should pull players in even if they’re not already experts on the history of the Jedi or the nature of the Maiar, I feel that if Hogwarts Legacy is going to work, it should work for newcomers as well as those who once loved the series so much that they got Harry Potter tattoos they now regret.

Also, lastly, this is not a review. Like a number of other outlets, we weren’t furnished with early code, in what I can only assume was an effort to ensure that early reactions to the game would be mostly positive. Of course, you may argue that it’s the role of publishers and publicists to cultivate good press for their games, but I wish they would see the value of the games crit ecosystem as not so much an extension of their own PR efforts to be gamed for positive buzz, but as a place that lifts up the medium of games as a whole by taking them seriously. Without the extra time that early code would have afforded me, I wasn’t able to finish the story or come close to fully exploring the world. Instead, I’ve spent around 15 hours with the game, enough to feel like I have a solid foundation upon which to base my impressions.

Enrolling at Hogwarts

The first thing you do in Hogwarts Legacy is create and name your character, so I created just the person I’d want to be if I were a British youngster being whisked off to grand adventures at a school of magic. I named her Emily Endecott, and gave her the kind of short, androgynous haircut that I sometimes wish I could pull off in real life without making myself that much more likely to be misgendered.

The game, to its credit, isn’t the least bit restrictive about gender presentation or identity. You can combine the character creator’s offerings of body types, hairstyles, voices and so on any which way you like, without it limiting whether you ultimately tell the game that you’re a “witch” or a “wizard.” And interestingly, whatever you choose, when other characters refer to you in the third person, they do so with the pronoun “they.” Of course, this choice was almost certainly made to simplify the game’s dialogue, eliminating the need for variations of the same lines based on gender, but if you so desired, it would allow you to headcanon that you’re playing as Hogwarts’ first nonbinary student.

After a bit of misadventure that works as a tutorial and suggests that you may be a Hogwarts student with rare and remarkable gifts (try to contain your shock), you arrive at the titular school, and it makes a grand first impression. I know that many people who grew up loving the Harry Potter books have dreamed of a video game that would let you live out your own life as a Hogwarts student. I’m not one of those people, but I’m still taken in by the rich detail and immersive atmosphere with which the school is recreated here.

The halls of Hogwarts have that hushed quality that so many old academic institutions seem to exude, making me feel like I’m walking the grounds of a building that already, even in the 1890s, has a grand and illustrious history. It is also, of course, unlike any actual school that has ever existed, filled with paintings that move, statues of wizards and dragons, a poltergeist practicing juggling while hovering six feet off the floor, and more secrets and puzzles and collectibles than you can wave a wand at.

The school’s grounds are vast, but they are also just one small part of Hogwarts Legacy’s world, which extends not just to the nearby town of Hogsmeade but to the surrounding valley containing the Forbidden Forest, other hamlets, dungeons, and points of interest to discover. You won’t get much environmental variation—it’s all Scottish countryside, after all—but it’s beautiful, and the landscape visually and tonally shifts through different seasons as the story progresses. Hogwarts Legacy does, at the least, deliver on the promise of making you feel like you are there, free to explore to your heart’s content.

Conventional combat in magical garb

Indeed, Hogwarts Legacy makes a great first impression. The atmospheric detail of its world is wonderful. However, across the remainder of my time with the game, a growing feeling crept in that underneath that layer of magic and whimsy were the bones of a decent but very conventional open-world game. In combat, for instance, a flash of gold around your head means an enemy is about to strike with a blockable attack, so you’d best block…err, cast Protego…at just the right moment. Meanwhile a flash of crimson means an unblockable attack is inbound, so you’d best dodge-roll out of the way like a typical third-person action hero. It feels a good deal like the combat in so many games these days, everything from Arkham Asylum to God of War Ragnarök, though not nearly as impactful as either.

Your primary means of doing damage is with your “basic cast,” a fizzy little bolt from your wand that has all the oomph of a typical video game pea shooter. (As far as I’m aware, this isn’t something that’s ever existed in the Wizarding World before, and was added just to fulfill the video-gamey requirement that you have a way to shoot things.) It’s underwhelming for sure, though this is done on purpose, to incentivize you to combine it with other magic. Hit an enemy with Levioso, for instance, and they may be helplessly held aloft in midair for a bit, and your magic cast will do bonus damage. Additionally, because of your connection to a rare kind of ancient magic, you can hurl environmental objects at enemies, and occasionally unleash attacks that do massive damage.

It’s not bad, but it’s also not special, and I’m disheartened by how many games, no matter what kind of world they take place in, are now using the same building blocks for their combat that we see in so many other games. (I laughed when I was introduced to the game’s “stealth kill” equivalent, which is just casting Petrificus Totalus while cloaked with a charm that makes you invisible.) Thankfully combat isn’t a particular focus here, at least in the first 15 hours or so, and you’ll likely spend a good deal more time doing other sorts of things, including adding a genuinely impressive assortment of spells to your arsenal. Most of what you do with those spells, however, isn’t particularly inspired. In a number of dungeons, you’ll find floating platforms that you can pull yourself around on using Accio. At first it’s a neat idea, but it soon starts to feel overused, as does a type of puzzle in which you must use Lumos to guide magical moths to various mechanisms.

A compelling story might also have helped me stay enchanted, but that, too, is quite ordinary and forgettable (when it’s not being outright awful). Initially, I’d hoped that I might be in for a real tale of friendship and self-discovery, elements that are key to the appeal and success of the original Harry Potter books, but though you meet a number of classmates and occasionally go on quests with them, they hardly become your Hermione or Ron, and your experience at Hogwarts feels strangely solitary. Sure, you can visit the common room of whatever house the sorting hat puts you into (or whichever one you choose for yourself if you don’t like the hat’s decision), but the Room of Requirement, where you can set up and decorate your own private little study room like a magical version of The Sims, is your real home at Hogwarts.

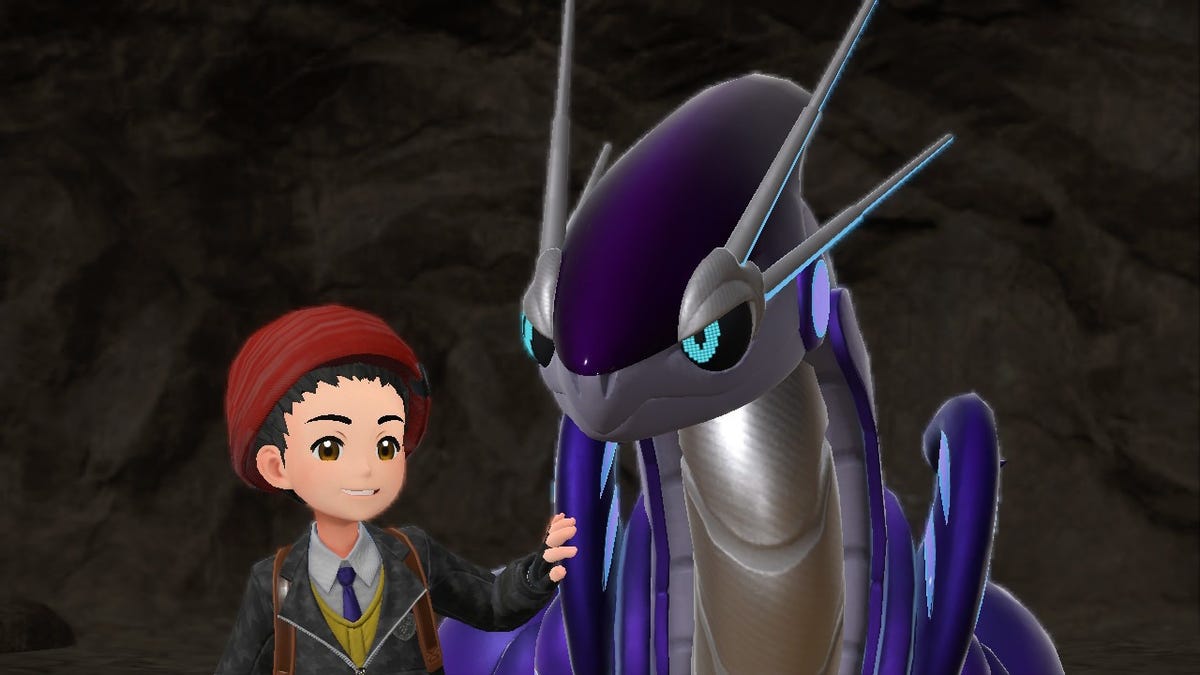

Though no one aspect of Hogwarts Legacy’s gameplay is particularly strong, it does make up for that somewhat by offering enough variety to keep you engaged. You can put a good deal of time and effort into activities like potion-making and herbology if you so desire, collecting recipes, seeds, and ingredients for an assortment of helpful concoctions and magical plants to aid you in combat. You can also capture…sorry, rescue…a variety of magical beasts who provide you with items you can use to upgrade your clothing, increasing your offensive and defensive stats and giving you other beneficial traits.

Admittedly, I haven’t put much time into this yet, but I do like how, from the Room of Requirement, you can step right into a vast vivarium that serves as a new home for the creatures you’ve collected. Moments like that, where vast spaces exist within smaller ones and where doors open from one realm into another, entirely different one, are little reminders of the wonder that’s possible when Hogwarts Legacy isn’t going through the open-world game motions.

There’s something rotten at Hogwarts

Right around the 15-hour mark, I have my first experience riding a hippogriff. A friend and I rescue two of them from poachers, and as we make our escape from their vile clutches, soaring atop the majestic creatures, the Hogwarts Express winds its way across the countryside far below. It’s an exhilarating and memorable moment, viewing the wizarding world from afar, with all of its messy complications neatly out of sight. The good guys are good, the bad guys are bad, and the train chugs by beneath us, the perfect picturesque little detail.

But the reality is that in Rowling’s world, and by extension, in Hogwarts Legacy, things aren’t nearly so clear-cut. That’s not inherently a bad thing, I like some moral ambiguity in my art, but the art has to engage with that ambiguity. What Hogwarts Legacy does, thus far anyway, is present a world filled with moral horrors and contradictions but then sort of shrug its shoulders and say this is just the way things are. You may see a house elf tirelessly scrubbing the floor as you head to class, and as you get near, he’ll disappear in a whirl of magic, not wanting you, the all-important human wizard, to concern yourself with the toil of those lowly, insignificant beings who work to maintain your immaculate surroundings.

Perhaps even more glaring for me is the way the game navigates goblins. There’s little argument, it seems, about the fact that goblins are not treated as equals by wizards. This strikes me as inherently bad. One of the game’s main antagonists, a goblin named Ranrok, agrees with me. However, his problem is that he “goes too far,” resorting to violence in his pursuit of goblin liberation. This is such a common tactic for films and games to use. They create a villain who has reasonable objections to the shitty status quo, but they resort to violence in their efforts to change things, so that the heroes can then work to protect the shitty status quo under the guise of stopping that villain, we as viewers or players can feel good about it, and the problems with the status quo are never addressed.

Early in Hogwarts Legacy, I meet a goblin named Arn, whose carts have been stolen by Ranrok’s loyalists after they peg him as a goblin who’s not sympathetic enough to the cause. He functions as a kind of mouthpiece for the game’s awful moral stance. He says “Many of us would like a diplomatic end to the discord with wizardkind,” and while I don’t think violence is generally the way for oppressed groups to seek liberation, I also know that asking nicely definitely isn’t, that power concedes nothing without a demand.

Later, after I help return his stolen carts, Arn, who is a painter, says:

The way this mentality erases the systemic issue of how goblins are discriminated against by wizards makes me want to scream. If an individual cis person is nice to me, I’m not going to dismiss the reality that transphobia exists and create some work that speaks to “the good” between trans and cis people. No, I want cis people to do nothing less than collectively work to dismantle transphobia, just as I want white people to collectively be traitors to the social construct of whiteness and dismantle white supremacy, just as I want every group that benefits from an existing oppressive system to dismantle that system.

What Arn is effectively saying here is that it’s okay that wizards systematically keep goblins on a lower rung of society because hey, he gets along okay with wizards like you! I don’t necessarily expect the narrative of Hogwarts Legacy to be about your character taking up the righteous cause of dismantling these oppressions, but I expect it to acknowledge and foreground that the real problem is that they exist in the first place, not that someone may be “going too far” in an effort to undo them.

It’s Rowling’s world, we’re just living in it

But again, this is Rowling’s world, a world where protecting the status quo is noble, where a Black magical cop is called Kingsley Shacklebolt, where maybe one house elf every now and then can get her freedom as a treat, but where the real bad guys are the goblins or trans people demanding equality and liberation from those who oppress them with all the power of money and institutions and entrenched social prejudices behind them, resulting in those oppressors needing to be defended.

This awareness has drained all the magic from the world of Hogwarts Legacy for me. It’s shortsighted, it’s centrist, it’s crushingly ordinary, the same way that forces like racism and transphobia are the most ordinary, tiresome things in the world. If there’s any real magic in the world, it lies in the ability to see that we don’t need these things, that they hold us all back, and that if we all want it badly enough and fight for it and leave behind the ones who tell us that this is the way things have to be, a better world is possible.

I knew that Hogwarts Legacy was going to be a hit. I knew it would sell bajillions of copies, that people who claim to be committed to the cause of trans rights would still gladly buy their $70 ticket to the virtual amusement park that J.K. Rowling built, all while muttering their mealy-mouthed excuses about how there’s “no ethical consumption under capitalism.” Yes, the game has a trans woman in it who you can’t miss. Yes, your character can defy gender norms. Here’s my position on that: It doesn’t matter. You know how Audre Lorde said “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”?

Hogwarts, and the whole wizarding world, are both the tools and the house of J.K. Rowling. They have made her unfathomably wealthy. They have granted her the bully pulpit she now uses to propagate anti-trans sentiment far and wide, making the lives of a marginalized and powerless minority who just want to live our lives in safety and dignity all the more difficult and dangerous, all while cultivating an image of herself–again, a billionaire–as a victim. I won’t link to it here, but as I write this, just yesterday The New York Times published an opinion piece titled “In Defense of J.K. Rowling,” just a few days after a 16-year-old trans girl was murdered in Rowling’s native UK. Maybe the transphobic billionaire isn’t the one who needs defending.

Yes, Hogwarts Legacy was made by a team of people, many of whom doubtless oppose Rowling’s views. In creating the world of the game, I cannot deny that I think that team did good work and should be commended. But the Wizarding World (™) is a corporate empire that sprang from the mind of Rowling. It enriches her at every turn. Liberation cannot be found there. Indeed, some of Rowling’s worst supporters are touting the game’s success as a success for anti-trans ideology itself, a win for the “anti-wokeness” set, where “wokeness” is simply the idea that we all deserve to exist in a society that sees us and treats us as fully human.